A lack of understanding costs the lives of many rock fishermen and boaties every year. It is also the cause of many rescues of swimmers from flash rips. When these large waves hit the beach the massive volume of water has to find its way back out to sea and can / does very easily drag unwary swimmers with it.

Predicting the size of the wind-generated waves that roll in from the sea around Australia is not as hard as you might think—especially if you understand the concept of ‘significant wave height’.

While

down at the beach or out on the water you will experience a wide range

of wave heights during your activity, and occasionally a genuine ‘big

one’, the fabled "rogue", "bomb" or "wave of the day". However wonderful

a prospect they are to surfers, big waves can pose a serious danger to

boaters and fishermen—particularly when they arrive at reefs, bar

crossings and deep-water coastlines, where the first indication of a

wave’s true size can be as it breaks on the rocks where you’re standing.

These are the rock fisher killers and the reason rock fishing is

Australia's most dangerous sport. They are also the cause of many boat

capsizes and sinkings due to the simple face that the anchor chain /

rope was not long enough to accommodate the big one.

The

size and behavior of waves are determined by a range of factors, from

the direction of the swell to the speed of the tide, prevailing ocean

currents, the depth of the water, the shape of the seafloor, the

presence of reefs and sandbanks, even the temperature of the ocean. Ever

wondered why on a very large beach all the surfers are crowded into the

one or two spots? Well know you know, they have located "The Bank" and

are using it to get a good ride. The surfers will also show you where

the rips are. They use them as an ocean elevator to get a free ride back

out the back for their next ride...

However,

there is one factor that rules the size of the waves more than any

other—the wind. Waves are caused by wind blowing over the surface of the

ocean and transferring energy from the atmosphere to the water. The

height of waves is determined by the speed of the wind, how long it

blows, and crucially the ‘fetch’—the distance that the wind blows in a

single direction over the water.

Naturally,

bigger waves result from conditions that cause strong winds to blow for

a sustained period over a large expanse of ocean. The resulting waves

can travel for hundreds or even thousands of kilometers, smaller waves

being absorbed by larger ones, faster waves overtaking slower—gradually

growing and arranging themselves into the regular ‘sets’ so familiar to

lifeguards, surfers and paddle-boarders. Understanding this along with

wave periods, assists the lifeguard to pick the best time and location

to head out for a rescue.

The result of these interactions is that it is normal to experience a wide range of wave heights when on the water.

A universal convention to measure wave height

Utilising

the standard international convention, the Bureau uses the concept of

‘significant wave height’ to notify ocean-goers of the size of swell and

wind waves (or ‘sea waves’) in its coastal forecasts. Significant wave

height is defined as the average wave height, from trough to crest, of

the highest one-third of the waves.

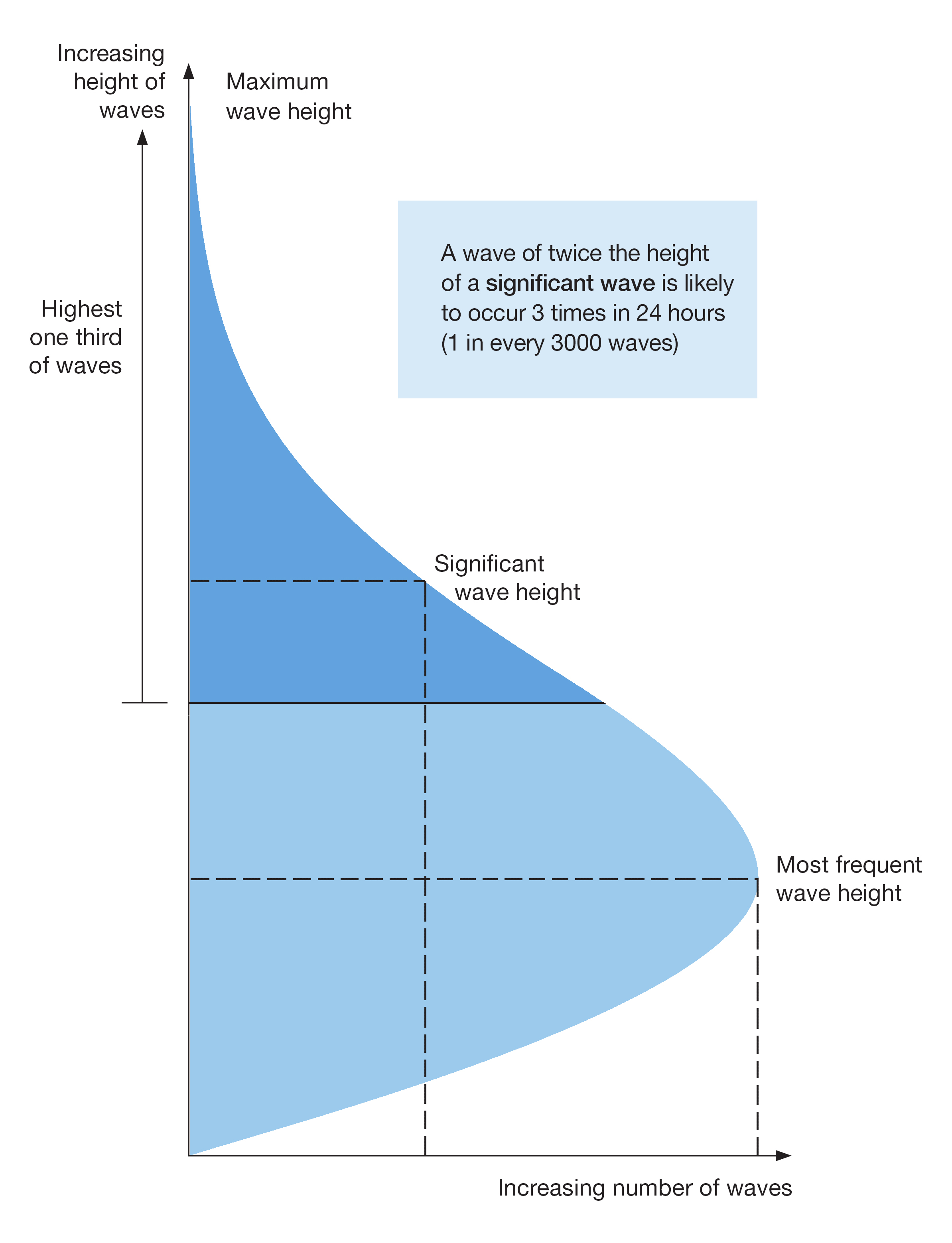

Devised

by oceanographer Walter Munk during World War II, the significant wave

height provides an estimation of wave heights recorded by a trained

observer from a fixed point at sea. As the following graph shows, a

sailor or surfer will experience a typical ‘wave spectrum’ during their

activity, containing a low number of small waves (at the bottom) and a

low number of very large waves (at the top). The greatest number of

waves is indicated by the widest area of the spectrum curve.

The

highest one-third of waves is highlighted in dark blue in the graph

below, and the average height of waves in this group is the significant wave height:

Significant wave height

This

statistical concept can be used to estimate several parameters of the

waves in a specific forecast. The highest ten per cent of the waves are

roughly equal to 1.3 times the significant wave height, and the likely

maximum wave height will be roughly double the significant height. So,

if you are going rock fishing or anchoring your boat near a reef etc,

remember it is not good enough to simply look at one or two waves and

she will right mate.....it won't be, allow for the bombs or pay the

ultimate sacrifice. No matter how good and how fast the lifeguards are,

sometimes we will not be able to save you.

Expect double the height, three times a day

While

the most common waves are lower than the significant wave height, it is

statistically possible to encounter a wave that is much

higher—especially if you are out in the water for a long time. It is

estimated that approximately one in every 3000 waves will reach twice

the height of the significant wave height—roughly equivalent to three

times every 24 hours. As a reminder of this important safety concept,

the Bureau includes a message that maximum waves may be twice the

significant wave height in all marine forecasts.

Most frequent, 'significant' and maximum wave heights

When

planning a voyage, mariners should not focus exclusively on the

significant wave height in a forecast. It is equally important to

recognise the concept of the wave spectrum, know the definition of

significant wave height, and be able to determine the expected range of

wave heights.

Much

like the median house price guide in the real estate sector, the

significant wave height is intended as an indicative guide that can help

you gauge the range of wave sizes in a specific area. While sailors can

use the figure to evaluate the safety of an open-water voyage, surfers

may use it to rate the likelihood of at least one ‘big one’ arriving

while they’re out in the surf. Rock fishers should also be aware of the

dangers of the ‘big one’ washing them off the rocks.

Wave forecasts in Australia

Wave

height information for seas and swells is included in the Bureau’s

Coastal Waters and Local Waters forecasts, covering the Australian

coastline and capital city waterways. These forecasts are also

transmitted by marine radio (HF and VHF).

Maps and tables of swell and wind wave heights are also available on MetEye—the

Bureau’s interactive weather-mapping tool—which allows mariners to

‘play the weather forwards’ over a specific stretch of water for the

coming week.

More information on MetEye’s wind and wave features can be found in these recent articles:

More information

About marine weather services: Information on the Bureau’s marine forecasts and terminology.

Preparing for your trip: Boating tips from the Australia New Zealand Safe Boating Education Group.

Important

note: Please be aware that wind gusts can be 40 percent stronger than

the averages given in coastal forecasts, while maximum waves may be up

to twice the significant wave height.